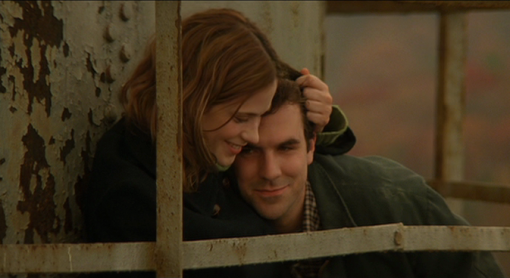

Two-Lane Blacktop (Hellman, 1971)

Men are machines. We are engines screaming down the hot asphalt, expressionless. We smell of octane, and rust with age, and we’re fueled by all the spit and blood of every man before us that tried to mold us into something strong, fast, and unrelenting. We flex our muscles with every engine rev, and our steely eyed glares cut through the night. We are not of flesh, but of steel and grease, made for one moment to rise, then fall, and then laid to rest in a quiet, grassy yard.

Perhaps that isn’t the essence of Monte Hellman’s meditative road film, but in each sad eyed, far off stare of The Mechanic (Dennis Wilson) and The Driver (James Taylor) one can’t help but feel a sense of detachment. These two men, machines, are more in tune with the sound of the screaming engine, and the hiss of the road under the tires then they are with any human kind. Even the Girl (Laurie Bird) aching to belong to something, and blindly pawing for love, can’t warm the flesh that binds the machine.

Then there is the character of G.T.O (Warren Oates). He is a rusted machine, clinging to his final coughing breaths of exhaust as he limps down the road. With each tale he spins you get a sense of a man searching for his humanity, so much so that he makes a mockery of it. He wants his moment in the sun. He wants to hear the engine howl one last vicious song, and then slump into the waiting arms of something he will never understand.

Does The Driver see this fate in the end of the film? There is a brief moment when he sees several old neglected cars behind a barn. Does he look off at the cars and read their rusted epitaphs and wonder “is it too late?”

– James Merolla

You must be logged in to post a comment.